By Daniel Cluskey, product stewardship engineer, Printpack

Increased attention on flexible packaging’s end-of-life is resulting in a massive shift to alternative forms of packaging. Twenty percent of the world’s packaging currently is controlled by CPGs with commitments to use recyclable, reusable or compostable packaging by 2025. While the packaging is changing, the requirements for performance remain the same. This provides opportunities for companies that can add value to the next generation of packaging substrates.

This paper will focus on challenges in the area of sustainable food packaging. Paper, monomaterial polyethylene and compostable substrates are on the rise, but transitioning from traditional substrates to these more-sustainable alternatives can be a challenge for CPG customers. Before 2025, gaps need to close between these new substrates and the incumbents with regard to barrier, heat-sealability and material toughness. Brands and converters are on the lookout for innovative partners who can help them solve these challenges.

Editor’s Note: This paper is based on a presentation at the 2020 AIMCAL R2R USA / SPE FlexPackCon® Virtual Conference, held online in October 2020.

Introduction

The flexible packaging industry has a Herculean task to achieve by 2025. Flexible packaging grew at a rapid pace during the past few decades because of its versatility and efficiency. Complex combinations of polymers, metals and coatings allowed engineers to craft packaging to meet all sorts of design challenges, from acidic ketchup and microwavable vegetables to heavy dog food. Each new development came with its own set of design criteria and was matched by innovative combinations of materials. Now, with Consumer Packaged Goods companies (CPGs) signing agreements to make all their packaging recyclable, reusable or compostable by 2025, the complexity of these multi-material structures will make them difficult to replace.

Although the agreements companies are signing outline Recyclable, Compostable or Reusable as viable options for future packaging, this article will focus specifically on recyclability in the United States. There is more than enough content around compostable and reusable packaging to fill another article. To keep the scope reasonable, this article will take a deep dive into recyclability.

It’s a start

In the US, the polyethylene store drop-off stream is the only method of collecting and recycling flexible packaging at scale. This consists of bins located in front of grocery stores to collect plastic shopping bags, bread bags, dry cleaning bags and other polyethylene packaging. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) states in its Green Guides that to consider a package recyclable it must be “…collected, separated or otherwise recovered from the waste stream through an established recycling program for reuse or use in manufacturing or assembling another item.”

Curbside collection of flexible packaging is being piloted, but in a vast majority of communities, store drop-off is the only near-term way to meet this requirement for the material to be collected. Once the material is collected and separated through the store drop-off stream, most of it is reprocessed into plastic lumber or some other durable good. This process of collection through the drop-off stream and reprocessing back into another product thus meets requirements outlined by the FTC for the material to be labeled as recyclable.

Monomaterial-PE use a serious challenge

To be eligible for the store drop-off recycling stream, a package must be made entirely of polyethylene (PE). That requirement is a massive blow to the toolbox of innovative solutions that packaging engineers have called on for decades. One of the biggest advantages of flexible packaging is the ability to combine dissimilar materials into a single structure that performs better than the sum of its parts. A standup pouch, for example, can be sealed so easily because it has a heat-resistant polyester layer on the outside and a polyethylene layer with a very low melting point on the inside, creating a wide window for sealing on packaging equipment. Many barrier films use different layers to protect the product from oxygen and moisture. Using only polyethylene to achieve everything that once was accomplished with a large toolbox of polymers and coatings will be a big challenge.

But this sustainability trend cannot be ignored just because it is challenging. As of last summer, the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, one of the largest NGOs focused on plastic packaging, had more than 200 businesses signed on representing 20% of all the plastic packaging produced globally. That number has grown since then. Signing on to the Ellen MacArthur “New Plastics Economy” includes a commitment to transition to recyclable, compostable or reusable packaging by 2025. Businesses that join this agreement actively look for suppliers that can help them meet the commitments they have made to transition to recyclable packaging. If CPGs meet the targets they have committed to by joining the foundation, any plastic-packaging manufacturer that is not able to provide recyclable packaging is in danger of losing market share to those that can. Sometimes, this even may result in CPGs sacrificing other packaging-performance criteria for the sake of recyclability.

Ranking what’s important

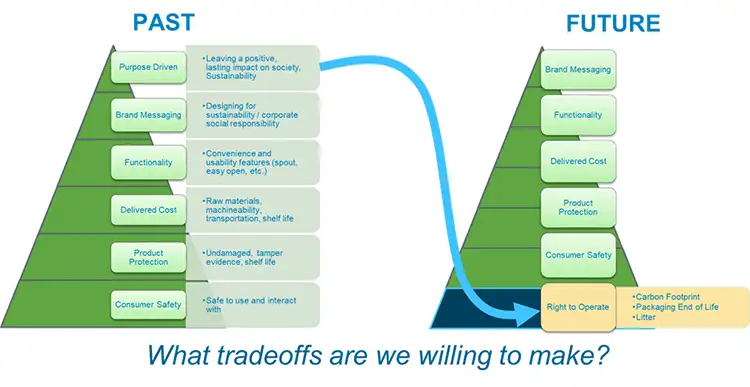

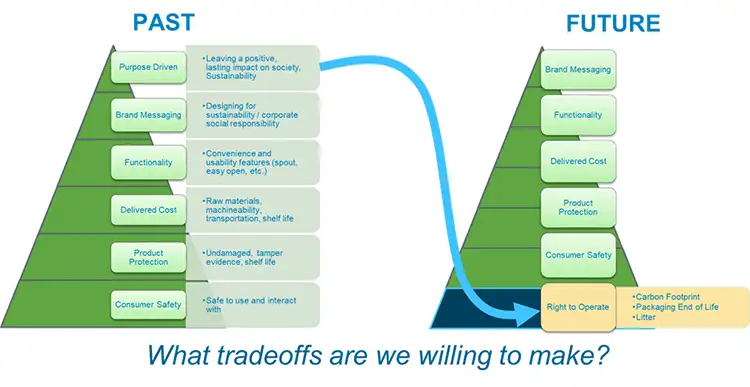

The reason companies are making this shift is best understood through the example of Maslow’s “Hierarchy of Needs.” If you recall your college philosophy class, you will remember that Maslow’s Hierarchy is a pyramid with basic human needs listed from bottom to top. The idea is that humans are motivated by their lowest unmet need. If you do not have your physiological needs met – like food, shelter and water – you are unable to move to higher levels on the hierarchy – such as love and belonging or self-actualization. CPGs also have a hierarchy of needs when it comes to their packaging. In the past, safety and product protection were firmly at the bottom, followed by cost and functionality. Then, if all those were met, the company could start worrying about brand messaging and the “purpose” of the brand.

Now, consumers are demanding more from the brands they buy. They don’t just want to buy a product; they want to support a brand that lines up with their values. In response, CPGs are realizing that a certain amount of purpose needs to be inserted at the bottom of the hierarchy to justify their right to operate in the market. If consumers are not buying a product because they do not agree with the brand’s purpose, then the CPG does not even get a chance to provide them with a safe and enjoyable experience (see Figure 1).

Three key development areas

Often this reprioritization results in tradeoffs. As purpose moves to the bottom of the hierarchy, other aspects of the package become less important as brands move to satisfy that unmet need. Even as CPGs become more willing to make sacrifices in packaging performance, significant areas exist where recyclable packaging still is not sufficient. The toolbox needs to be rebuilt with recyclable materials so packaging engineers can design the next generation of recyclable products. The three biggest areas where development is needed are heat-resistance, barrier and appearance of the package.

Heat-resistance is a big challenge when dealing with polyethylene films. As mentioned before, with multi-material laminations, a heat-resistant outer layer can be laminated onto a structure to stop it from melting, stretching or distorting when it runs on high-speed packaging equipment. With a toolbox using only polyethylene, creative solutions are needed to provide heat-resistance. Orientation is one promising development path being explored. Oriented polyethylene provides heat-resistance and dimensional stability beyond what a blown or cast polyethylene film can provide and sometimes produces a wide enough heat-seal window to run efficiently on packaging lines. For applications where oriented polyethylene is not enough, heat-resistant coatings that do not interfere with the recycling stream may be needed to give that final few degrees of protection to make a package run. If CPGs are not able to run the packaging on their equipment, it will not matter how recyclable the material is because it cannot fulfill its purpose.

The next big hurdle to overcome with all polyethylene packaging is barrier. Multi-material packaging has a wide range of products to provide the oxygen, moisture and light barrier required to keep products fresh for extended periods of time. Just to name a few: Metallized films provide excellent light barrier, EVOH provides oxygen barrier and polypropylenes often are used for moisture barrier. All three are considered contaminants in the store drop-off recycling stream. One method of getting these tools back is through compatibilizing technologies. Compatibilizers allow non-polyethylene resins to mix with polyethylene in the recycling stream and are a great way to bring barrier polymers back into the development toolbox. Barrier coatings also will play a part in future packaging because they can provide a barrier while making up only a very small portion of the package. In both cases, these non-polyethylene components must be managed in a way that does not negatively impact the recycling stream.

Finally, appearance is key for CPG customers that want to make the switch to recyclable packaging. Consumers still expect high clarity, matte appearances and textured coatings that are possible with multi-material packaging. Consumers have a strong belief that matte products are more sustainable than glossy ones. If a recyclable glossy package and a non-recyclable matte package are sitting next to each other on a shelf, they could be confused about which product is more sustainable. Versions of these products that are compatible with the PE-recycling stream will be critical going forward.

With all these new technologies, the most important thing is that any new innovations not negatively impact the recycling stream. Materials are only recyclable if someone is willing to buy them, so making sure that only compatible materials end up in the store drop-off recycle stream is the top priority of any development. The industry has a long road to transition from our current state into recyclable packaging. However, I am confident that we will rise to the challenge and innovate the next generation of recyclable, heat-resistant, barrier packaging that provides great appearance.

Daniel Cluskey, product stewardship engineer in Printpack’s Office of Sustainability (Atlanta, GA), works to create products approved for the recycling stream. A 2016 chemical engineering graduate of Villanova University, he started his career with Printpack as a product development engineer. For four years, Daniel led development on technical projects related to microwavable frozen vegetables, child-resistant packaging for laundry packs, chemically resistant packages for pool chemicals and single-serve condiment packages. In the Office of Sustainability, he expands Printpack’s recyclable-product portfolio and works with customers to identify the best solutions to their sustainable-packaging needs. Daniel can be reached at 404-460-7221, cell: 412-735-9518, email: dcluskey@printpack.com, www.printpack.com.