Does flexible packaging truly have a future in the circular economy?

By Pierre Sarazin, Ph.D., Ing., vp-R&D and Sustainability, PolyExpert, Inc.*

Editor’s Note: This technical paper is based on the author’s presentation from the 2022 AIMCAL R2R USA Conference held Oct. 25-29 in Orlando, FL.

Introduction

The Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s (EMF) first reports in 2016-2017 [1] created an unprecedented awareness among the public and all stakeholders in the value chain of packaging and single-use plastics. Actions to solve plastic waste and plastic pollution had been neglected for decades. It also had been decades since all the fundamentals of the circular economy had been outlined, but there was very little action as of yet. At the technical level, the principles of sustainable-materials management gradually have been replaced by the (broader?) vision of the circular economy.

In theory (and as Pierre Desproges said: one day I will go and live in theory because in theory everything goes well), the circular economy aims to decouple economic growth from the depletion of natural resources and its impacts on the environment through two main mechanisms [2]: 1) by rethinking our production-consumption patterns to consume fewer resources and protect the ecosystems that generate them; and 2) by optimizing the use of resources that already circulate in our societies and taking action on waste and pollution.

After being ignored for so long, the fight against plastic pollution suddenly has taken the spotlight. Under this momentum and since 2018, national and regional pacts as well as the Global Commitment (GC) were created, with very similar targets and some differences in the levels to be achieved [3]. As early as 2019, Kantar’s “Who Cares, Who does?” survey [4] revealed that plastic waste had become the second-biggest concern of consumers on average. It came right after climate change and just before water pollution – far ahead from a range of other concerns, such as water shortages, air pollution, waste of food and deforestation. The message “If the current trend continues, there could be more plastic than fish (by weight) in the ocean by 2050” was a strong image supporting the cause, which was, however, not properly supported by studies [5]. Nevertheless, it was taken up by the media and at least twice during the UN General Assemblies with headlines such as “At last the tide is turning on plastic” and “We must save our world from drowning in plastic” [6]. This kind of strong image has the merit of highlighting global waste mismanagement (of which plastics are only a part), but it also accentuates denigration of plastics and its repercussions in today’s political decisions.

However, we can note a good catching up of the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) in 2021 [7]: simply banning single-use plastic products and switching to single-use products made of other materials is not the solution. They support that “it is the single-use nature of products that is the most problematic for the planet, more so than the material that they’re made of.” A paper shopping bag may need to be used four to eight times to have a lower environmental impact than one single-use plastic bag, the message explains. Well said! Now, as we begin talking about a global treaty on plastic pollution, where are we on the Global Commitment targets for flexible packaging?

2022: The year Ellen MacArthur Foundation dropped the circularity of flexible packaging

(aka 2022: The year EMF decided to prioritize fighting plastic waste instead of acting to reduce climate change)

The Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF) published its fourth progress report last November [8], which covers the year 2021. While representing more than 20% of the packaging market, here are the key findings of the report:

“The target of 100% reusable, recyclable or compostable plastic packaging will almost certainly be missed by most organisations, with flexible packaging and lack of infrastructure being the main barrier.”

“Business-to-consumer flexible plastic packaging – e.g. sachets, wrappers, small bags – is the fastest-growing packaging category, with very low recycling rates and a disproportionate share of environmental leakage. It represents 16% of signatories’ plastic-packaging portfolios by weight, but up to 30% to 40% of the total global plastic packaging weight.”

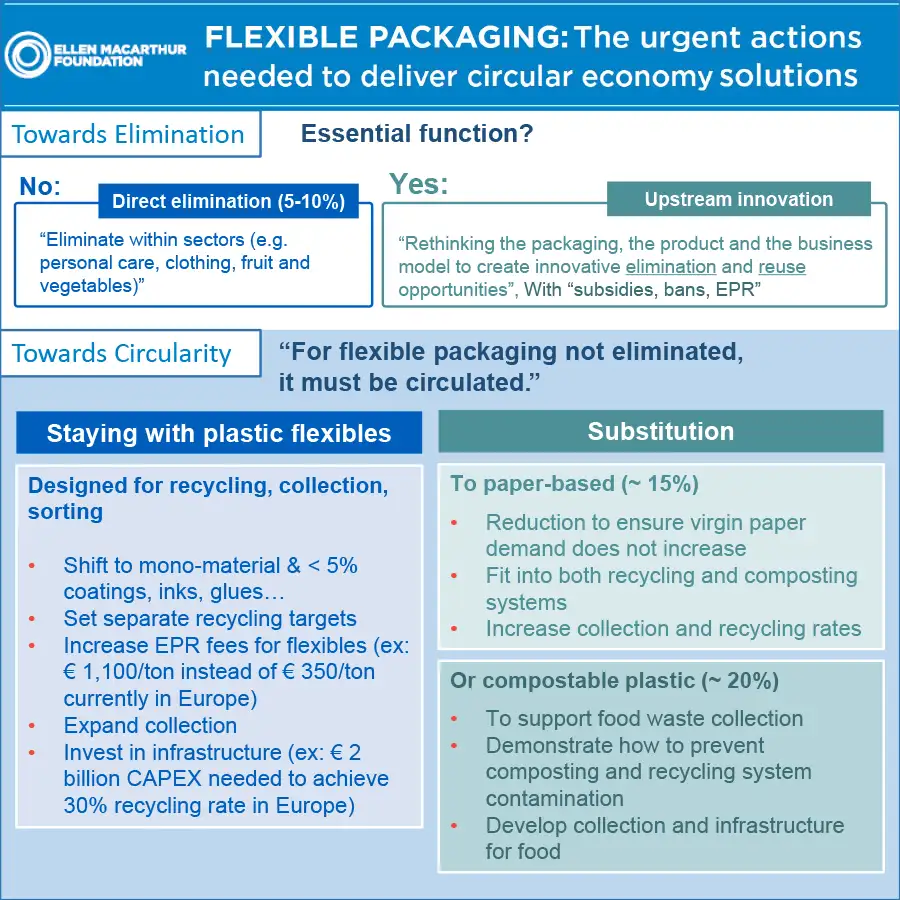

Flexible packaging “is increasingly unlikely to meet recyclability in practice and at scale by 2025.” It is therefore necessary to take exceptional measures on flexible plastic packaging and the foundation recommends innovating away from this type of packaging (see Figure 1).

Already in 2021, the report stated that “many signatories face significant challenges meeting their 2025 targets due to having large proportions of currently non-recyclable packaging types, in particular flexible packaging, in their portfolios.” Among the signatories, the food sector, for which at least 48% of packaging is flexible, had the lowest average recyclability. According to EMF, the overall situation for the global plastic-packaging market is as follows: about 30% by weight recyclable and supported only by rigid packaging. Although flexible packaging remains, in our opinion, the most favorable alternative to reduce the use of resources (materials, transport, carbon footprint, etc.), its main weakness concerns material circularity; the packaging rarely is collected nor recycled. Thus, the Foundation is focusing on non-flexible solutions, such as reusable and rigid packaging.

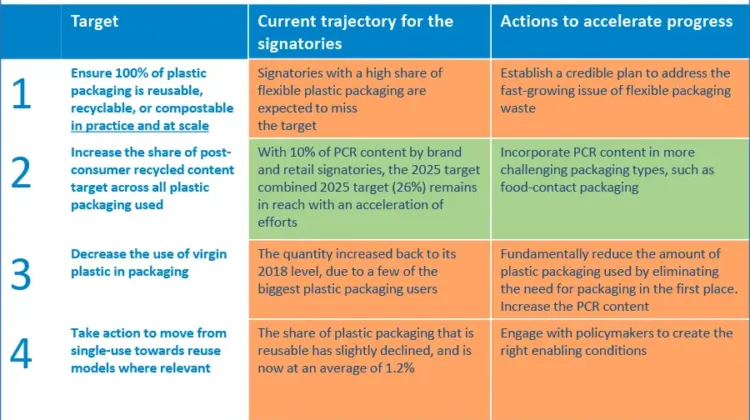

Key progress metrics for flexible plastic packaging

We summarize key progress metrics based on the well-known Global Commitment targets and a non-exhaustive list of actions to take (see Figure 2). In our opinion, this is the first report where we see first-hand the actual limits of implementing the circular economy for packaging. Even with a balance of signatories – half of the number represents brand owners, retailers and governments, and the other half the plastics industry – the targets mainly are aimed at packaging as seen by consumers and thus are placed at the level of brand owners, retailers and governments. All the rest of the supply chain appears as a black box. This is even more evident when looking at actions for reuse models which focus mostly on the end of the value chain; there always will have been packaging before, even if we eliminate the final packaging to please the consumer. In fact, the actions on packaging that make the most sense are in foodservice (take-away food), while it still is necessary to ensure that the environmental impact will be to a lower end. To attain the objective of having only reusable, recyclable or compostable plastic packaging, this is the first time, to our knowledge, that the progress report recommends the pure and simple elimination of flexible packaging.

Overall, there has been no real improvement in almost all key progress metrics since the start of the Global Commitment. The percentage of plastic packaging that is reusable, recyclable or compostable has remained virtually unchanged over the past few years, and for good reason – what was easily recycled already had been captured in the first place. The amount of virgin plastic used in packaging has remained stable, and the percentage by total weight of reusable packaging still is close to 1%.

While there were many examples of elimination of plastic packaging that was considered “problematic or unnecessary,” only 22% of these examples involved a fundamental change to packaging, product or business-model design to avoid the use of single-use packaging. This is not a success in the sense of what the Foundation expected. In many cases, the elimination of plastic was done through material substitution, using paper, aluminum, glass or another to replace plastics. While being perceived as more appealing in consumers’ eyes, it does not solve the problem of single-use items.

On the other hand, packaging manufacturers’ efforts revolved mostly around making plastics more recyclable; using fewer pigments or additives; using more mono-materials; or lightweighting (52% of the examples). The only success to date is the increase in post-consumer recycled (PCR) content, which has doubled to 10%. This is obviously still very low, but the 2025 target remains attainable. One particularly challenging application is food-contact packaging, for which incorporating recycled plastics currently is hard to achieve for materials other than PET. The same is true for flexible packaging. In many countries, the use of mechanically recycled plastics in food packaging is prohibited, limiting its progress. Beyond the technical challenge of incorporating recycled content into other packaging types, the high price and limited supply of recycled plastics were reported as key barriers.

Can flexible packaging really be eliminated?

Overall, the EMF report highlights a multitude of actions to reduce plastic waste, however, they do not reflect the desired profound change in packaging through redesign, innovation and new delivery models. We have studied in more detail the series of documents published on March 31, 2022, by the Foundation [9] during our last presentation at the 2022 AIMCAL R2R USA Conference [10]. To summarize, two elimination paths have been identified: 1) the direct elimination of plastic packaging; and 2) the elimination by upstream innovation (see Figure 3).

In our opinion, some eliminations may make sense, but the scope of the actions remains very limited. As for upstream innovation, the ideas proposed for packaging can be surprising: water-soluble packaging (is the disappearance of packaging by dissolution an acceptable solution? Not sure at all [11]); reusable glass packaging for refill for dried food (and the pasta arrives without packaging in the delivery truck?); and edible coatings. Is the functionality of packaging well understood? All these examples concern the packaging itself, but what about product innovation? Only one example describes product innovation: moving personal- and home-care products from a liquid form to a solid product, which allows reduction of volume and affects the type of packaging needed. More examples like this one should be proposed to demonstrate that a systems approach can be more impactful, by rethinking products rather than rethinking only packaging.

If elimination is not possible, design for recycling/collection/sorting still is appropriate and substitution to other materials is presented as an alternative. The US Plastics Pact stated in early 2022 [12], “When considering substitution to a non-plastic material such as paper, glass or metal, the packaging will be considered out of scope for the US Plastics Pact.” Thus, substitution by eliminating plastic appears to be the easiest way to fulfill these commitments (and often by increasing the amount of material used). The examples described in the report for substitution with flexible compostable or paper-based packaging are very limited. EMF thinks that going back to paper packaging is a better solution than plastic for bread and dried food & cereals, pasta, rice. Globally, it is true that the recycling of paper packaging is 60% compared to only 10% for plastic packaging. However, do they share the same functionality? We can question the understanding of the functionality of the packaging, and in any case, the carbon footprint is not considered.

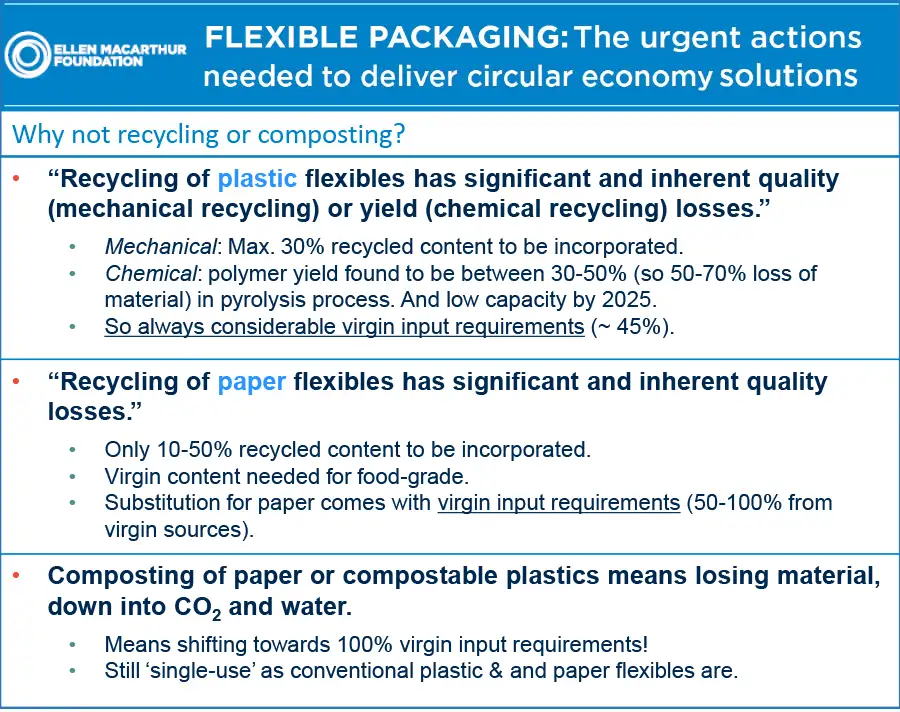

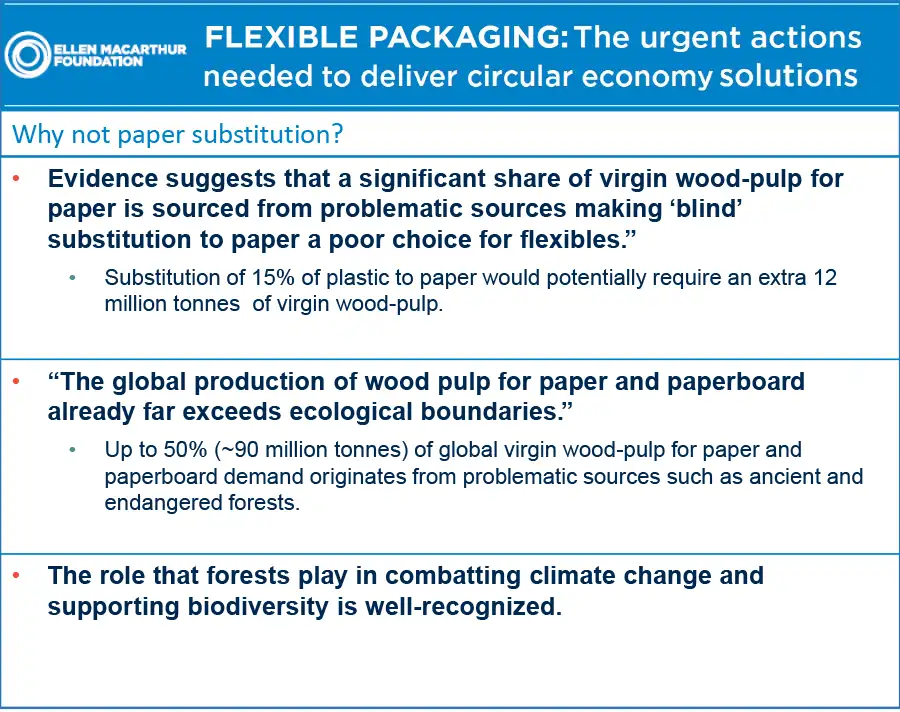

Afterwards, EMF brings to our attention that recycling and composting are not sufficient solutions as they always will require use of virgin materials, be it plastic or paper (see Figure 4). Finally, to confirm that flexible packaging should really be avoided, whether it is plastic or paper, EMF argues that plastic substitution to flexible-paper packaging should be prevented as it will increase the demand for wood pulp, when our use of forest resources already is unsustainable (see Figure 5).

Where are the life cycle analyses?

The most surprising element of these conclusions is that they do not seem to account for life cycle analyses. Hosted by UN Environment and being at the interface between users and experts of Life Cycle approaches, the Life Cycle Initiative [13] develops a series of meta-analyses of life cycle assessment (LCA) studies that provide recommendations to policymakers on alternatives to commonly used single-use plastic products.

Regarding the single-use plastic bag (SUPB), the report published in 2020 [14] of the meta-analysis of seven LCAs states that it is “a poor option in terms of litter on land, marine litter and microplastics, but it scores well in other environmental impact categories, such as climate change, acidification, eutrophication, water use and land use.” Moreover, they conclude that “paper bags contribute less to the impacts of littering but in most cases have a larger impact on the climate, eutrophication and acidification, compared to SUPBs.” According to them, “the overall environmental ranking will depend on what environmental aspects are given the highest priority. In this context, it might be important to note that bags are responsible for a significant share of the litter, but a very small share of total climate change when compared with other products and commodities.” A weakness is that the terms littering and microplastics often are used together in the report, whereas we find it difficult to argue that shopping plastic bags are one of the sources of microplastics.

More recently, UNEP’s study on the single-use supermarket food packaging [15] reminds us that packaging accounts for 31% of total plastic use, and that “on the North American market, plastic packaging accounts for 43% of the market share of rigid containers (tubs, trays, jars, non-beverage bottles, drums, etc.), 67% of flexible packaging (pouches, wrappers, bags, liners, etc.), 72% of caps and closures and 100% of films (stretch and shrink wrap, stretch labels, sleeves, etc.). The current common bias toward unpackaged and reusable packaging as the ideal solution is noticeable, but the study is very much qualified by science-based (and common sense) principles. The key messages, full of wisdom, are presented in Figure 6. We must not dissociate the packaging from its content. We need to explore the whole supply chain and using a system approach must be considered. Focusing only on packaging to reduce plastic packaging waste seems to be an aberration today.

Conclusion

Even if we question some of their recommendations, the EMF report helps to draw a picture of the global state of plastic-packaging circularity. Now, how does this translate to real-life actions? It is certain that the circular economy initially presented by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation was the driving force behind the actions taken by the flexible-packaging industry and governments. Our second article will look at what we can see today regarding actions underway and their results.

*The text was reviewed by Emma Sarazin, Master student in Environmental Management at the University of Sherbrooke, Quebec, Canada. The information, figures and opinions in this article are the sole responsibility of the author. While we strive to be as unbiased and objective as possible, please inform the author of any inaccuracies or misunderstandings.

References

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation, The New Plastics Economy: Rethinking the future of plastics, published in January 2016, and The New Plastics Economy: Catalysing action, published in January 2017, https://ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/topics/plastics/projects

- Québec Circulaire, Issues and Definition, https://www.quebeccirculaire.org/static/h/issues-and-definition.html

- The Plastics Pact Network, https://ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/the-plastics-pact-network

- Kantar, Worldpanel, “Who Cares, Who does?” Consumer response to plastic waste, Sept. 2019, https://www.kantarworldpanel.com/global/News/Who-Cares,-Who-Does-Consumer-response-to-plastic-waste#download

- A.Warin and P. Sarazin, Between opinions and certainty: A fact-based approach to flexible-packaging sustainability, 2021 AIMCAL R2R USA Conference and SPE FlexPackCon®, Oct. 21, citing: Hornak, L. (2016). Will there be more fish or plastic in the sea in 2050?, BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-35562253; Jambeck, J. R., Geyer, R., Wilcox, C., Siegler, T. R., Perryman, M., Andrady, A., Narayan, R. & Law, K. L. (2015). Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean. Science, 347(6223), 768-771. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1260352; Jennings, S., Mélin, F., Blanchard, J. L., Forster, R. M., Dulvy, N. K., & Wilson, R. W. (2008). Global-scale predictions of community and ecosystem properties from simple ecological theory. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 275(1641), 1375-1383. https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/pdf/10.1098/rspb.2008.0192

- https://www.un.org/pga/73/2018/12/18/op-ed-at-last-the-tide-is-turning-on-plastic/,

https://www.un.org/pga/73/2019/06/05/op-ed-we-must-save-our-world-from-drowning-in-plastic - UNEP, Nov. 2021, How to reduce the impacts of single-use plastic products

https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/how-reduce-impacts-single-use-plastic-products - https://ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/global-commitment-2022/overview

- https://ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/flexible-packaging/overview

- P. Sarazin, 2022, Three Years Before a Deadline, 2022 AIMCAL R2R USA Conference, Orlando, FL, Sept. 26-29.

- As an example, read the article in Plastics News: Groups want EPA to limit PVA in laundry pods, seeing microplastic problems, https://www.plasticsnews.com/public-policy/cut-microplastic-leaks-groups-want-epa-limit-cleaning-pods

- The US Plastics Pact’s Problematic and Unnecessary Materials Report, Jan 25, 2022.

https://usplasticspact.org/problematic-materials/ - https://www.lifecycleinitiative.org/activities/key-programme-areas/technical-policy-advice/single-use-plastic-products-studies/

- United Nations Environment Programme, 2020. Single-use plastic bags and their alternatives – Recommendations from Life Cycle Assessments, https://www.lifecycleinitiative.org/library/single-use-plastic-bags-and-their-alternatives-recommendations-from-life-cycle-assessments/

- United Nations Environment Programme, 2022. Advance copy: Single-use supermarket food packaging and its alternatives: Recommendations from life cycle Assessments. Nairobi. https://www.lifecycleinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/UNEP-D010-Food-Packaging-Report_Final-Version-1-1.pdf

Editor’s Note: Read the author’s second article in this series, “Governments and industry progress toward flexible-packaging circularity,” online at www.convertingquarterly.com.

Pierre Sarazin, vp-R&D and Sustainability at PolyExpert, Inc. (Laval, Quebec, Canada), is a member of SPE Flexible Packaging Division. He holds a Ph.D. in Chemical Engineering from Ecole Polytechnique Montreal, and is the co-author of 20 journal publications, several patents and patent applications. Pierre has gained experience in bioplastics and then plastics along with an in-depth understanding of formulations tailored for various processing technologies. He also is a member of the Scientific Advisory Committee of the CREPEC (Research Center for High Performance Polymer and Composite Systems, Quebec, Canada). Pierre can be reached at www.linkedin.com/in/pierresarazin.