By Sage M. Schissel, Ph.D., applications specialist, PCT EB and Integration, LLC

Sustainable practices, including material reduction and the use of bio-based, recyclable or compostable materials, are forefront in the minds of both consumers and the packaging industry. This especially is true for flexible packaging, which traditionally has consisted of multilayer, non-recyclable structures. In this study, the use of electron-beam (EB) technology in the life cycle of a compostable, flexible package was investigated.

Editor’s Note: This technical paper originally was published in UV+EB Technology, 2020 Q2, pages 14-20. It since has been updated with newly expanded experimental-test results. Part 1 covered how EB curing aids the mono-material trend, degradation of materials by EB chain-scission and the experimental setup.

Results and Discussion

The purpose of this study is to establish EB-curable, overprint varnishes (OPVs) can be used in the production of compostable, flexible food packaging without significantly impeding the compostability of the packaging. Furthermore, EB exposure was investigated as a means of accelerating the disintegration during composting. High doses were used to weaken the compostable film through chain-scission.

Packaging compostability

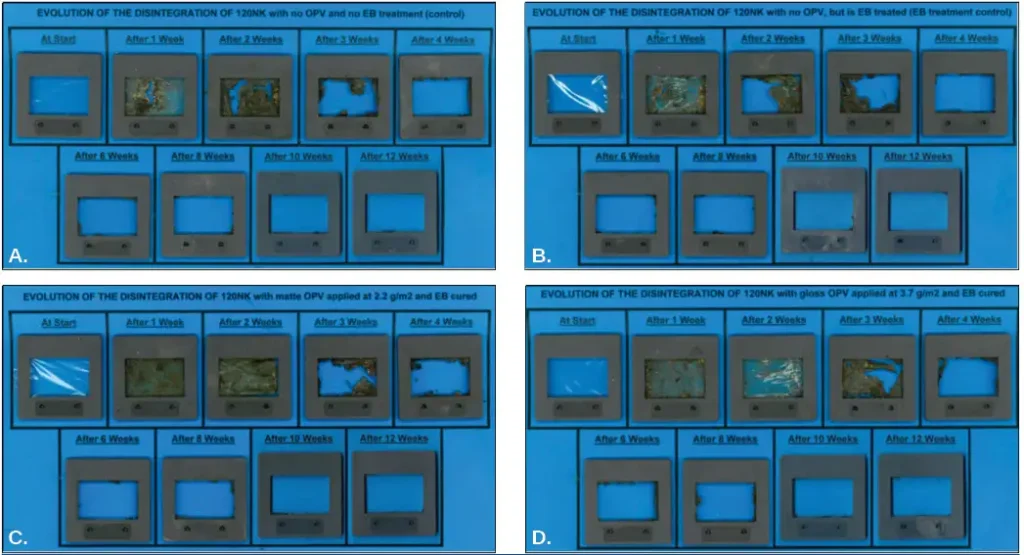

An integral aspect of using EB-cured OPVs in compostable flexible packaging is demonstrating that the OPVs do not inhibit or significantly impede the disintegration of the compostable film. In addition, because EB is well known to interact with cellulose, it is also important to establish what effect an EB curing dose (30 kGy) has on the compostability of the film [21,29]. To this end, select samples (see Table 1 in Part 1) were composted and their disintegration progress visually documented (see Figures 1A-D).

Comparing the control film (see Figure 1A) to a film that’s received a curing level dose (B), the EB dose does not appear to have a significant effect. After two weeks of composting, the EB sample (1B) appears to have slightly more disintegration than the control (1A), but those impressions flip after three weeks. After four weeks, both samples almost are completely disintegrated, with only a few small pieces of film still left at the edges of the test frame.

The addition of an EC-cured OPV also does not appear to significantly impact the disintegration time of the film. The majority of both the EM-coated (see Figure 1C) and EG-coated (1D) samples was disintegrated after four weeks. Both samples retained slightly more film at the edges of the test frame after four weeks than the control (1A); however, by the end of six weeks (a five-week photo not being included in the test results), the disintegration levels of the OPV-coated samples and the control are visually the same.

Post-treatment of packaging

With the compostability testing providing positive qualitative results and demonstrating that EB-cured OPVs can be effectively used in the production of compostable, flexible food packaging, the potential of EB technology to affect a package after consumer use was considered. Composting, even on an industrial scale with controlled conditions, is a time-intensive, multi-week process. Accelerating the disintegration of material could allow compost facilities to efficiently convert a higher volume of packaging with little to no changes in infrastructure.

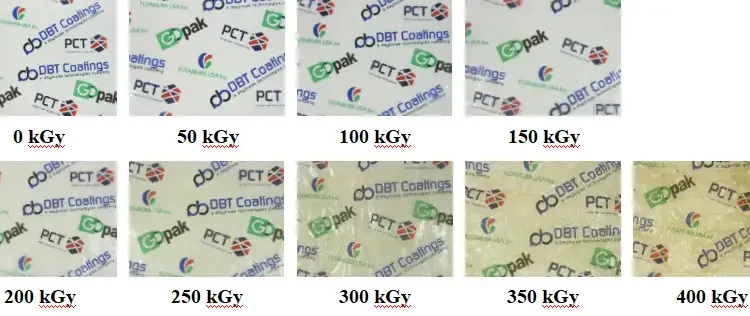

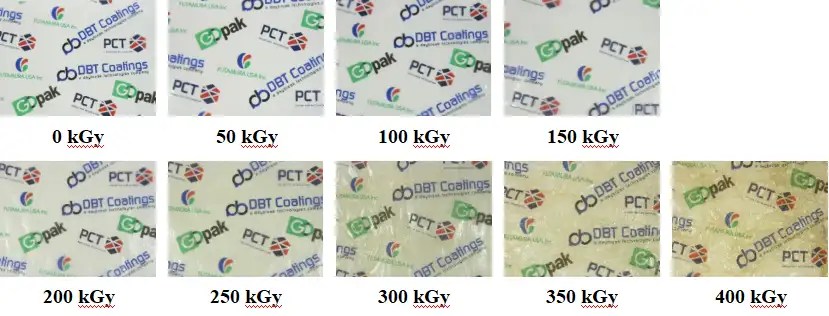

Visual effects: The degradation of the compostable packaging structure (film/print/OPV), caused by EB irradiation, was first evaluated visually (see Figure 2). Samples exposed to an EB post-treatment dose of 50 to 400 kGy were compared to a control (see Figure 2, 0 kGy).

Remarkably, there are no discernible effects of the EB post-treatment until 150 kGy. At 150 kGy, there is some slight discoloration of the film and noticeable cracking of the OPV. As higher post-treatment doses are applied, the yellowing of the film intensifies and the film shrinks and wrinkles.

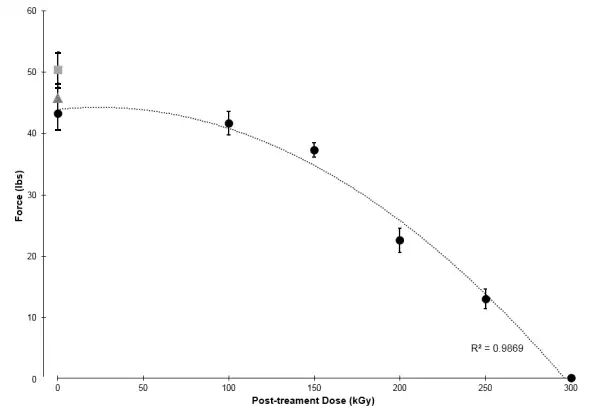

Puncture-strength reduction: Puncture strength was used as a quantitative measure of the scissioning effect caused by high doses of EB. As chain-scission increases, the strength of the film is expected to decrease. Figure 3 shows a clear correlation between the puncture resistance of the compostable film and the dose level of the EB post-treatment. Comparing the plain NK120 film to the plain film after receiving a curing-level dose (see Figure 3, grey square and triangle, respectively), there is an approximately 5-lb decrease in puncture resistance. Note, there is some overlap of the error in these measures. No significant difference is seen when print and EG OPV are added to the construction (black circle, 0 kGy). As the EB post-treatment dose is increased, the puncture force decreases. The relationship of these two variables follows the trend line of a second-order polynomial with an R2 value of 0.9869.

Interestingly, there is almost no loss of puncture resistance between the 0 kGy and 100 kGy post-treatment dose. While EB dose levels generally are kept quite low for curing (~30 kGy), this result, along with the visual results, demonstrates that there potentially is a much larger EB operating window than previously thought. The effect of EB on other mechanical properties would need to be investigated to confirm. However, a larger operating window could be a beneficial option for improving ink and coating performance through enhanced crosslinking.

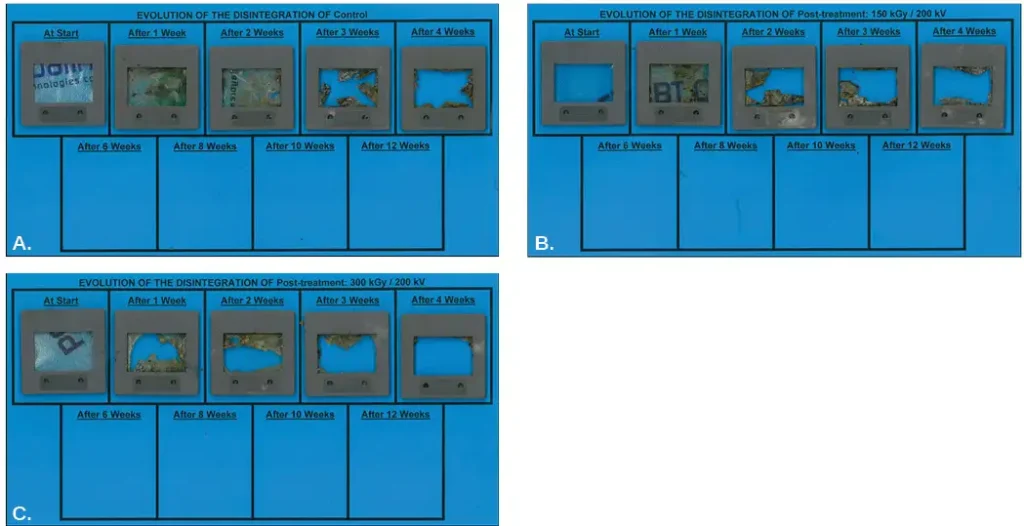

Compost results: Based on the results of the puncture-strength testing, three samples were chosen to test the effect of EB post-treatment on the compost rate of the packaging structure, a control and two different post-treatment doses (see Table 2 in Part 1). Significant differences between the samples were observed (see Figures 4A-C).

After one week, the control and 150-kGy post-treatment samples turned brown, but no disintegration had yet occurred. Contrastingly, the 300-kGy post-treatment sample already had experienced a significant amount of disintegration. After two weeks, a large portion of the 150-kGy post-treatment sample had disintegrated, while the control sample still was almost completely intact. Similar amounts of material remain between three and six weeks for the control and 150-kGy post-treatment samples, until both appear fully disintegrated at eight weeks. The 300-kGy post-treatment sample appears almost fully disintegrated, with only a few remnants in the sample frame, as early as four weeks. From these results, using a high-dose EB post-treatment to increase the rate of disintegration of compostable material looks promising.

Conclusions

A qualitative compostability test was conducted and showed that EB-cured OPV did not make a significant impact on the compost rate of a cellulose film. These results indicate that the reviewed structures would likely pass a quantitative, mass-balance test.

Furthermore, a post-treatment EB dose was evaluated as a potential means of increasing the composting rate of the flexible-packaging structure. The degradation of the film was confirmed visually as well as by demonstrating that puncture strength decreased as the post-treatment dose was increased. The qualitative compostability testing of these post-treated structures showed high-dose EB post-treatment positively impacts the composting rate.

In addition to quantitative compostability testing, future work in this area includes broadening the scope of OPVs, inks and compostable substrates investigated. The optimal EB dose necessary to degrade a compostable structure is expected to be dependent on the chemistry of the film and also should be evaluated for a wide variety of compostable material.

The broad applicability of EB was demonstrated by establishing the technology as a tool for both the production of compostable packaging as well as the degradation of it after use. As the packaging industry endeavors toward a more sustainable future, versatile technologies, such as EB-curing technology, provide companies flexibility in developing new avenues to achieve their recycling and composting targets.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge DBT Coatings for initiating and funding the first round of compostability testing and sharing the results. These data provided the impetus for further exploration of EB’s role in compostable packaging. The author also would like to acknowledge Futamura for donating the NK120 film and GOpak for donating printing-press time and materials.

References

21. Driscoll, M., Stipanovic, A., Winter, W., Cheng, K., Manning, M., Spiese, J., Galloway, R.A., Cleland, M.R., 2009. Electron-beam irradiation of cellulose. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 78, 539-542.

29. Zivanovic, S., 2015. Electron-beam processing to improve the functionality of biodegradable food packaging. In: Pillai, S.D., Shayanfar, S. (Eds.), Electron-beam pasteurization and complementary food-processing technologies. Woodhead Publishing, Boston, pp. 279-294.

Sage Schissel, an applications specialist at PCT EB and Integration (Davenport, IA), holds of Bachelor’s degree in Engineering Science from Wartburg College, and a Ph.D. in Chemical and Biochemical Engineering from the University of Iowa. She introduces customers to electron-beam technology and works with them to enhance existing processes by using EB or to develop entirely new processes and applications. Sage has been involved in EB research for the past 10 years. She can be reached at 563-285-7411, ext. 4429, Sage.Schissel@pctebi.com, www.pctebi.com.