By Pierre Sarazin, Ph.D., dir.-R&D, PolyExpert, Inc., and Emma Sarazin, Business Administration student

Editor’s Note: This article has been adapted from presentations at the AIMCAL R2R USA / SPE FlexPackCon 2019 conferences, held in Myrtle Beach, SC, in October 2019, titled “Flexible Plastic Packaging Sustainability: Will the Industry be Ready for 2025?” and “Flexible Food Packaging in the Context of Circular Economy.”

Abstract

In the last few years, the concern about plastics use has been rising within the growing environmental responsibility of the public. Following that same mindset, the Ellen MacArthur Foundation has been working for more than a decade on the development of a new model of economy, more respectful and responsible for our environment: the “Circular Economy.” In 2017, the Foundation started to address this issue by evaluating the problem of plastics, draw conclusions and propose actions to “Rethink plastics.” In October 2018, the Global Commitment was unveiled to create a concrete circular economy for plastic materials. The following article firstly aims at presenting the concept of circular economy and relates it to present work in the plastic industry, and secondly aims at arousing curiosity to dig deeper and generate a new creative mindset in flexible packaging.

There are more serious and urgent threats than plastic pollution

Concerns about the use of plastics and the environmental issues regarding its disposal have been rising within the public opinion. The last two years have demonstrated the delicate position to which the plastic industry has been confronted in response to this new concern from consumers. The industry suddenly felt vulnerable and unprepared for this outcry, even with the supporting presence of serious studies showing the benefits of plastic packaging. This confusion about plastics arises from the lack of information accessible to consumers about its use, particularly for retail goods.

This resulted in unfair attacks toward food packaging, especially in Europe and Canada, and thus motivates education efforts to address key issues such as: 1) The reason why plastic packaging is present at each stage of the food-processing value chain; 2) The serious consequences for the food supply without its packaging; and 3) The environmental cost of replacing plastic with another packaging type and material. If consumers point out instances of overpackaging in food, communication would be key to address the misunderstanding around the presence of the packaging and be able to provide a better packaging based on those consumers’ observations, if needed.

Based on our knowledge, we find food-overpackaging examples to be very rare as the problem usually is caused by an inappropriate application of the packaging instead of the packaging itself – for example, unskinned fruits in a plastic container. In fact, plastics tend to be the scapegoat for many environmental issues due to the visibility of its waste, disassociated from its real effect on global climate issues. As R. Stafford and P.J.S. Jones argue, “Plastic pollution has been overemphasised by the media, governments and ultimately the public as the major threat to marine environments at the expense of climate change and biodiversity loss.” [1].

Everybody agrees that ocean plastic pollution is a concern that needs to be addressed – and should have been a long time ago, as the situation was known and monitored for more than 30 years. However, the authors are convinced that “there is considerably less evidence of its effects at a planetary, ecological or toxicological level.” The elimination of single-use plastics might be positive – and we need facts to measure the extent of the progress achieved by this elimination – but it will not mitigate climate change.

The authors explain that Earth faces several major anthropogenic environmental threats caused by overconsumption of natural resources by a growing population. Changes in practices and policy pushed by anti-plastics campaigns fail to address the root cause of those environmental issues. They argue that “ocean plastic pollution has created a convenient truth to distract environmental policy from more serious and urgent threats.” To summarize, it is true that without action on plastics we might have more plastic residue than fish in the ocean by 2050, but we might not have any fish at all in the seas if drastic worldwide actions are inefficient to reduce overfishing itself and to slow climate changes, which, for example, incrementally reduce the oxygen in ocean water.

However, having this sort of global view is not an excuse to remain passive regarding plastic pollution. The flexible plastic industry must increase its efficiency to act on the sustainability of the products and services it provides. The industry has to be flawless on the design and manufacturing of plastic packaging as it has the potential to do so. The flexible-packaging industry soon could be a model for sustainability in other industries.

Circular economy: “River” vs. “lake” approaches

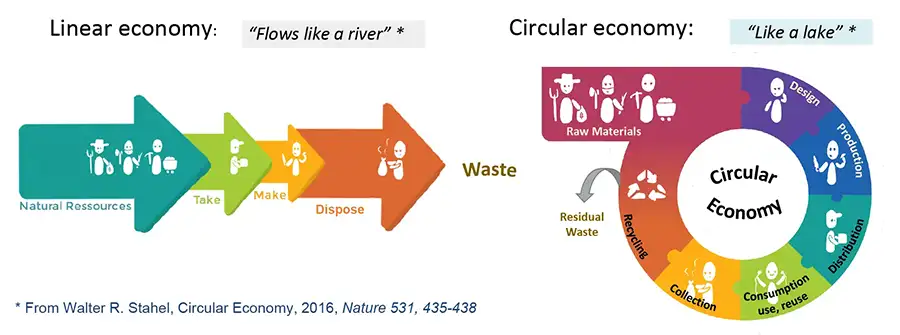

The circular economy is a concept that emerged in the 1980s and initially was elaborated by Walter R. Stahel, who illustrated the fundamental differences with the current linear production system. As stated by W.R. Stahel [2], “a linear economy flows like a river, turning natural resources into base materials and products for sale through a series of value-adding steps. At the point of sale, ownership and liability for risks and waste are passed to the buyer (who now is owner and user). This economy is driven by a “bigger-better-faster-safer” syndrome.

On the other hand, a circular economy is “like a lake” (see Figure 1). All the products manufactured ultimately will stay in the “lake” after use. The concept is built around the idea that goods have unlimited value, echoing nature’s own system in which there is no concept of waste [3]. Materials used for a certain product can be reused, recycled, repaired and/or remanufactured back into other goods. Instead of following the traditional linear path of extracting resources, creating a product and disposing of it once its useful life has expired, circular economy focuses on giving multiple lives to goods.

One key idea is to replace initial production of goods by what can be called secondary production, namely, everything done to extend the service life of the goods, such as repairing, remanufacturing, recycling, etc. – practices which, in theory, require fewer resources and less energy. This mechanism is referred to as “closing loops,” meaning that materials see no end to their service life: Once their main useful life is over, the goods serve as resources for other products, thus creating an endless loop. The focus shifts from creating cheap and disposable goods to long-lasting ones, contrasting profoundly with the current economic system.

The performance economy concept goes even further by focusing consumption on services to use the goods instead of buying them. The ownership of products in this model stays on the production side, thus giving incentive to manufacture long-lasting goods. Michelin is an example of that, selling tires “by the mile” to vehicles’ owners [2]. This type of model echoes in many ways the principles of sharing economy, characterized by the coordination of shared goods – for instance, cars and houses – on diverse platforms. The attraction of a circular economy is further demonstrated by showing benefits simultaneously at an economic, environmental and social level. Moreover, the model offers high perspectives for creating new employment opportunities. In this light, circular economy sounds like the ideal low-carbon model on every angle.

However, one of the main uncertainties of circular economy, addressed by T. Zink and R. Greyer [4], is to what extent the “closing the loop” process is realistically better. A cyclic flow does not automatically ensure sustainability and could have a serendipitous effect, which Zink and Greyer named the “circular economy rebound.” This rebound refers to the backfire of the circular model by an increase in production and demand for goods, hence leading to additional environmental impact. Part of this rebound effect comes from the extent to which the “closing the loop” model is applicable to all goods and services.

It also is hard to predict consumers’ reactions to extended product lifespan. Our current economic model encourages overconsumption by presenting cheap and attractive goods corresponding to seasonal or yearly trends. A circular model thus necessitates a change in individuals’ consumption behavior to favor use of long-lasting, second-hand and recycled goods. The body of literature on the topic is reaching a boiling point, and some references are full of insights, such as the book by Ken Webster [5] and the last work written by W.R. Stahel, released in June 2019 [6]. This latter one, for which the working title has been for a long time “Circular Economy for Beginners,” is essential to understand the concept of circular economy.

Rethinking the future of plastics

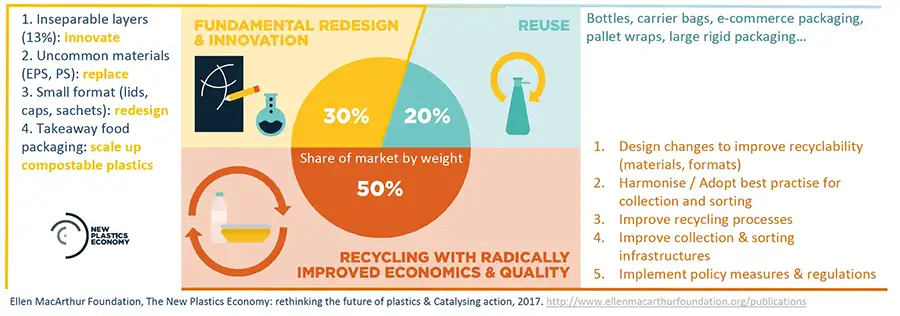

According to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation [7], product design is at the root of waste and pollution prevention. Around 80% of environmental impact comes from decisions made at the design stage of a good. In 2016/2017, the Ellen MacArthur Foundation proposed actions to “Rethink plastics” [8], among which companies working in flexible plastic packaging can find a lot of potential avenues to improve design and recyclability (see Figure 2).

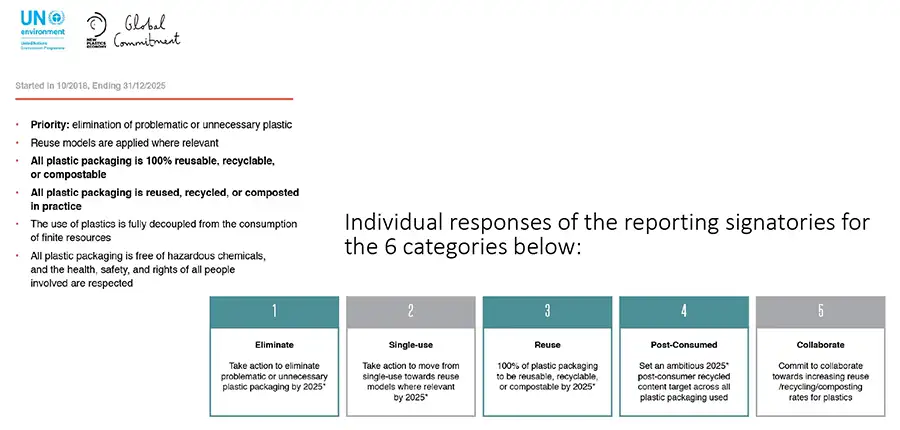

The report recommends innovation for products based on inseparable layers. A good example concerns the multilayer films needed for barrier performance. In October 2018, the New Plastics Economy (NPE) Global Commitment was unveiled to “offer a root-cause solution to plastic pollution with profound economic, environmental and societal benefits,” defining the circular economy by six characteristics (see Figure 3). So far, more than 400 organizations, counting among them more than 200 businesses representing over 20% of all the plastic packaging used globally, are part of this common vision. Flexible-plastic structures certainly are the most suitable to improve packaging sustainability while maintaining functional performance. The signatories’ commitments, split into five categories, then were reported in June and October 2019 [9] (see Figure 3).

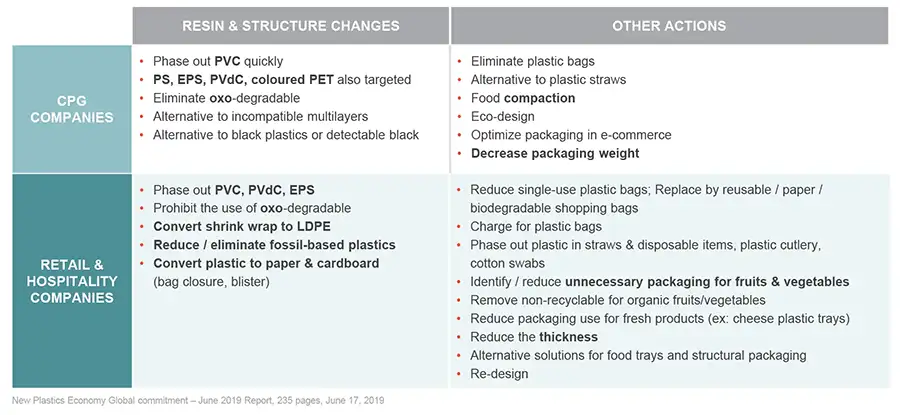

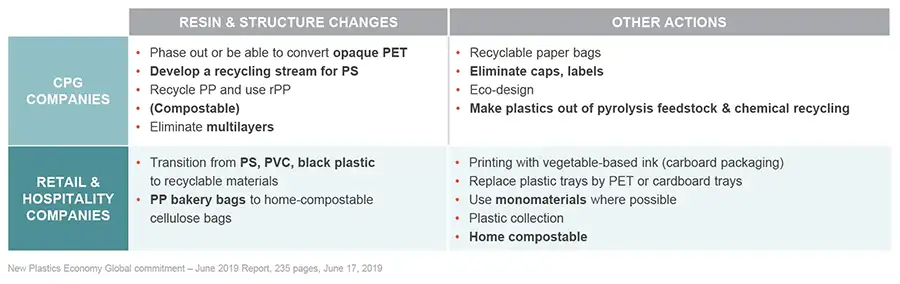

In our AIMCAL R2R USA / SPE FlexPackCon 2019 presentations, we focused on major CPG, Retail & Hospitality companies for their responses based on the June report noted above. We can see the declared will to take action on specific resins and alternatives for some problematic plastic packaging (see Tables 1-2). Will the industry be ready for 2025? So far, it is hard to say after just one year of the NPE Global Commitment.We are expecting more from the committed organizations, and future progress data will determine if we truly see a change.

The packaging manufacturers aside, a lot of concrete action currently has been taken in North America by a multitude of stakeholders, such as the Sustainable Packaging Coalition (SPC) [10] and one of its projects, How2Recycle [11], and some retailers, such as Walmart (we certainly are missing a lot of exceptional players and apologize for omitting them). Walmart recently introduced a new version of its Sustainable Packaging Playbook, a concrete initiative to support its suppliers [12]. Such global commitments can translate into practical strategies for companies of all sizes.

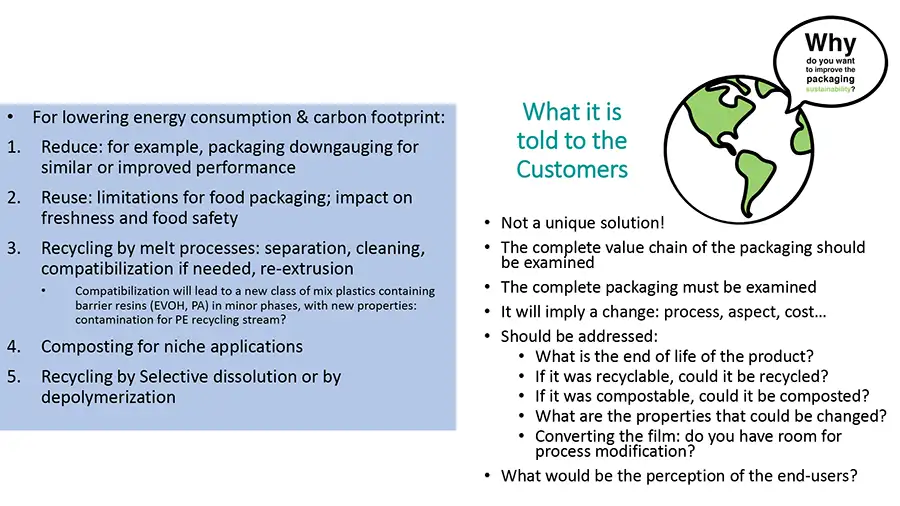

At our firm, a non-integrated blown-film manufacturing leader in sustainability and certified EcoResponsible TM Level 2 (Ecocert), the first action is to describe the possible options to customers requesting a “sustainable solution,” and film design will start only when the full life cycle of the product clearly is identified (see Figure 4). In fact, it necessitates to consider each of the stages of the circular economy and understand what the preferable end-of-life of the packaging product would be. In several cases, the discussion needed to be shared and extended with the customers of the clients. These clients could have concerns about disclosing those discussions or be reluctant to connect directly their supplier or with their customer, but ultimately experience shows that it always is a win-win situation to focus on sustainability. Indeed, it is important that the supplier itself, to the best of his or her knowledge, understands and is convinced that the suggested solution will be the best on the sustainability value for the customer. In this way, the client is not only buying a product, but also the whole service aiming at making that product more environmentally responsible.

A package of solutions

The sustainability in flexible plastic packaging is a work in progress, with a lot of tangible actions taken only recently. Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s NPE Global Commitment is clearly an impressive accelerator of the mindset. The solutions are in real-time development, even though we cannot determine so far which ones will emerge in a lasting way. It is both quite exciting and troubling to observe and act in this paradigm shift that looks like a “sustainable technologies bubble” where there will be winners and losers in that quest for sustainability.

Five years ago, who would have thought that metallized films would provide recyclable, high-barrier packaging, as claimed today by Celplast Metallized Products, Ltd.? Who would have thought that recycling by selective dissolution or by depolymerization would be so seriously considered? According to a report prepared by McKinsey & Company, nearly 60% of plastics production could be based on plastics reuse and recycling by 2050, and nearly 30% of plastics production could be provided from recovered monomer and recovered feedstock [13]. The discussion will continue this year among several significant conferences, including FPA, SPC, TAPPI IFPED, AIMCAL R2R / SPE FlexPackCon (see Events at www.convertingquarterly.com).

The plastic industry in its entirety is step-by-step, making significant moves, but this change needs to be supported with more regulations, from which will stem more logistics and more communication between companies partnering in the same loops. It could with time reinforce the flexible plastics industry, with new players entering the market – recycling technologies, life-cycle evaluation, etc. – generating more value with less waste and a reduced carbon footprint. It also could protect the North American market from new rules being enforced; for example, a minimum recycled content, or obligation to use a specific label – SPC’s drop-off label, Ecoresponsible certification [14].

But, don’t forget: The industry needs to be attentive to the proposed solutions and call them into question, in order that the globally adopted solutions are the best ones possible for society, the planet and future generations. We can see good ideas and not so good ideas. And today, we absolutely don’t know what the winning solutions will be at the end of 2025.

References

1. Richard Stafford, Peter J.S. Jones, Viewpoint – Ocean plastic pollution: A convenient but distracting truth?, Marine Policy, 103, 187-191, May 2019, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0308597X1830681X & Pierre Sarazin, LinkedIn Article, Nov. 29, 2019, https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/ocean-plastic-pollution-has-created-convenient-truth-distract-pierre/

2. Walter R. Stahel, Circular Economy, 2016, Nature 531, 435-438 https://www.nature.com/articles/531435a

3. Ellen MacArthur Foundation, Re-thinking Progress: The Circular Economy, video on YouTube, Aug. 28, 2011. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zCRKvDyyHmI&feature=emb_title

4. Trevor Zink, Roland Geyer, 2017, Circular Economy Rebound. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 21, 3, 593-602. June 2017, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jiec.12545

5. Ken Webster, The Circular Economy: A Wealth of Flows, Ellen MacArthur Foundation Publishing, 2nd Edition (Jan. 31, 2017) ISBN-10: 0992778468, ISBN-13: 978-0992778460, 202 pages

6. Walter R. Stahel, The Circular Economy: A User’s Guide, Routledge Publishing, 1 edition (June 10, 2019), ISBN-10: 0367200171, ISBN-13: 978-0367200176, 118 pages

7. Ellen MacArthur Foundation website. https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/circular-economy/what-is-the-circular-economy

8. Ellen MacArthur Foundation, The New Plastics Economy: rethinking the future of plastics & Catalysing action, 2017. http://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/publications

9. June and October reports can be downloaded at https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/our-work/activities/new-plastics-economy/global-commitment

10. https://sustainablepackaging.org/goals/

12. Walmart Sustainability Hub’s resources: https://www.walmartsustainabilityhub.com/packaging-and-plastics/resources. The links for the last “Recycling playbook” (Oct. 25, 2019) and a full of relevant information are available there.

13. Report, December 2018. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/chemicals/our-insights/how-plastics-waste-recycling-could-transform-the-chemical-industry

14. EcoResponsible Program includes a series of strategies and tools to support businesses or organizations looking to improve their sustainable development overall, and the certification is made by Group Ecocert. http://www.ecoresponsible.net/

Pierre Sarazin, dir.-R&D at PolyExpert, Inc. (Laval, Quebec, Canada), a Canadian leader in polyethylene blown-film manufacturing, is a member of SPE Flexible Packaging Division. He holds a Ph.D. in Chemical Engineering from Ecole Polytechnique Montreal, and is the co-author of 20 journal publications, several patents and patent applications. Sarazin has gained experience in bioplastics and then plastics along with an in-depth understanding of formulations tailored for various processing technologies. He also is a member of the Scientific Advisory Committee of the CREPEC (Research Center for High Performance Polymer and Composite Systems, Quebec, Canada). Sarazin can be reached at www.linkedin.com/in/pierresarazin.

Emma Sarazin, a Business Administration student at HEC Montreal and at the University of Amsterdam (UvA), is aiming to contribute to sustainable development. She wrote an essay titled “Circular Economy: its Potential and Limitations” in December 2019. She can be reached at www.linkedin.com/in/emma-sarazin-138b60175/.